A cautionary tale from a heart patient

I have originally set out to write a follow-up FB post to share my deeper reflections after a recent brush with death. It ended up as a long essay. I hope my wake-up call serves as a helpful cautionary tale for you to take your health more seriously.

A wake-up call

Three weeks ago, I was diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD). CAD is a condition in which the coronary arteries (the blood vessels that supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle) become narrowed or blocked due to atherosclerosis (plaque buildup). This restricts blood flow to the heart, leading to various complications, including angina (chest pain), heart attack, and heart failure.

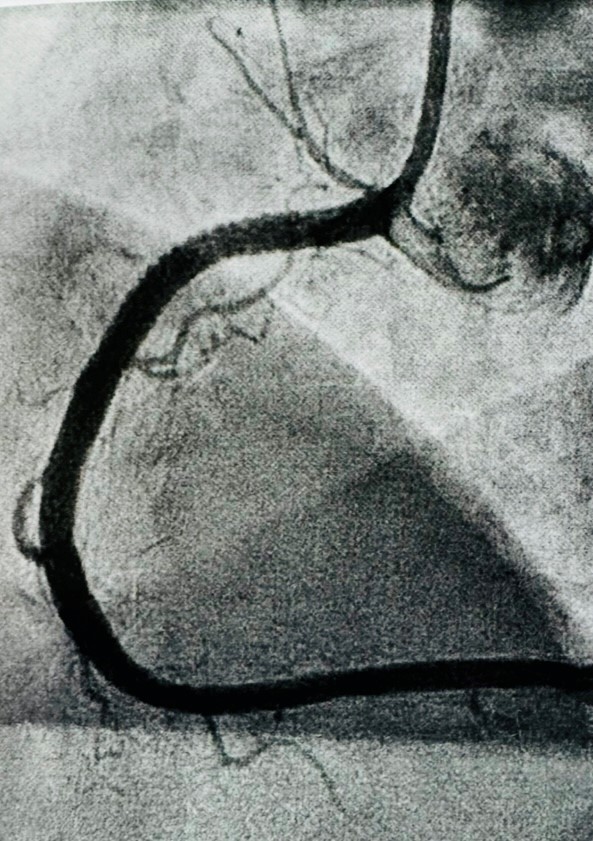

An angiogram revealed multiple blockages – 100% obstruction of the right artery, and 70% of the left. It’s a miracle that I’m still alive and kicking. I could have suffered a heart attack and dropped dead whilst swimming or hiking.

“Well, to die whilst doing what I love isn’t a bad thing,” I consoled myself. But at fifty-four, I’m not quite ready to kick the bucket. I’ve got a lot more to live for. And my early demise won’t be good for my family, especially my wife to whom I had vowed to grow old together.

[ Download PDF to read text with photos … ]

After two rounds of angioplasty (ballooning) and insertion of four stents to prevent the arteries from narrowing, I feel like a new man, albeit with an old heart. Through God’s grace, I’ve been given a new lease of life. And I’m not about to let it go to waste. If this wake-up call isn’t loud enough to get my act together and take my health seriously, I deserve to go to hell. I am not going to hit the snooze button this time.

I was once blind (to the conditions of my heart), and now I see. Lying on the table in the operating theatre, I could literally see the dye illuminating the blocked arteries. They looked like twisted ropes or branches on a tree, with some portions narrower than they should be.

A narrow escape

When the cardiologist turned to me and solemnly said, “I’ve got bad news,” I knew instantly that I was in for a shock. He had found a total seven blockages in three arteries, ranging from 40% to 100% obstruction.

The typical treatment for such conditions is angioplasty where a catheter is guided to the blocked area of the artery followed by inflating a small balloon at its tip to compress the plaque against the artery walls, widening the blood vessel. In many cases, a stent (a small wire mesh tube) is placed in the artery to keep it open.

However, he wasn’t completely confident that the chronic total obstruction (CTO) could be treated and referred me to a colleague who specialized in the more complex procedure needed. “The success rate is fifty-fifty,” he warned. Had that failed, a coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or heart bypass would be needed – meaning more invasive, higher risk of complications and mortality, and longer recovery time.

I was also informed that the operating theatre I was in for angiography was not ideal for what was to come next. To increase the likelihood of success, I was given the option to reschedule the procedure to another day when a more suitable room is available. But I didn’t want to wait any longer, and promptly replied, “I’ll take my chances. Let’s give it a shot today.”

The plan was to fix the fully obstructed right artery first, and then the left in the following week. The first angioplasty went smoothly. After an overnight observation, I was discharged the following day with two stents amounting to a total length of 66 mm and wounds in my groin and wrist.

Before first angioplasty After first angioplasty

Feeling relieved to have escaped the need for a heart bypass, I remained cautious not to celebrate too soon. The treatment is only halfway through. Thankfully, the second angioplasty went extremely well too. And as the catheter was inserted through the wrist instead of the groin, recovery was much easier. I could walk and was discharged the same day.

At last, I could commence my journey to recovery.

Never let a good crisis go to waste

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a famous saying by Winston Churchill that appeared frequently in the media. The words “Never let a good crisis go to waste” came to mind as I reflected on this recent heart-wrenching (literally) and awakening experience

I’m certainly not letting this crisis go to waste.

I’m determined to learn from this episode of ill-health and make some life-enhancing changes.

With four weeks of medical leave and supportive colleagues who stepped in readily to offload my work, I have ample time and space to unplug and truly slow down. Over the last few weeks, my mind has been traversing across three interconnected territories – the past, the present, and the future.

This dynamic mental dance is a free form movement with no rhythm or order. One moment, it’s beaming with ideas on changes I could make towards living a healthier life. Next, it darts to memories of me lying still on the operating table, viewing the X-ray images of ink flowing through my heart. And then to the present moment, fingers tapping on the keyboard, capturing my inner voices by spitting words on the computer screen.

For now, let’s begin with a reflection of the past.

Here’s how it all began …

A serendipitous nudge

Over dinner with friends who happened to work in healthcare, my wife casually asked if they knew any good cardiologist. Thanks to their recommendation, I landed an appointment at the National University Heart Centre within the same week.

Upon hearing my recent bouts of shortness of breath and reviewing my ECG charts, the cardiologist promptly booked me in for an angiogram the following week. An angiogram is a common medical procedure to diagnose coronary artery disease. It involves inserting a catheter into a blood vessel in the groin or wrist, followed by injecting a contrast dye to make the vessels visible on X-rays.

Whilst it is a generally safe procedure, it carries some minor risk of complications such as blood vessel injury, excessive bleeding, heart attack, infection, kidney damage due to the dye used, allergic reactions to the dye or medicines used during the test, and stroke. After explaining the risks, he asked if I would still like to proceed. Without hesitation, I said “Yes!” I’ve procrastinated long enough to get my heart examined and shall wait no more.

A week later, lo and behold, he looked over my shoulder and shared the bad news. My right artery is completely blocked, and the left is almost as bad.

Confronting mortality

I have had several health issues and undergone various surgeries in the last five years, but none as life-threatening as the heart disease that I now know I have. When the doctor rattled off the risks and probabilities for complications and death with the procedures, it suddenly dawned on me that I could potentially die.

My next trip to the hospital might be my last. Time’s up. Game over.

I started thinking about the arrangement I could make. Should I review my will? Should I write a letter to my wife and children and leave it somewhere they would easily find if I were to perish? Should I start sharing passwords for my bank accounts with them?

And then I stopped myself from going down the rabbit hole with these reasonably valid, yet unhelpful thoughts. Why plan for the 1% of failure instead of the 99% of success?

“All will be well. My family will be fine without me,” I affirmed myself.

Death is nothing to be feared or planned for. With that, my attention switched to the changes I would make towards living a healthier and more fulfilling life – starting with a heart-healthy diet.

How did I get here?

Heart disease is common. And it is preventable. In my case, having a heart with complete blockage undetected is shocking at first but absolutely plausible in hindsight. My mother had suffered a heart attack in her late fifties and undergone angioplasty with stenting too. I have simply followed her footsteps, albeit at a younger age.

Family medical history is a major predictor of heart diseases – one that I had conveniently ignored at the risk of my own peril. “I didn’t think that could happen to me,” could have been my famous last words. But no. I’d rather say,“I’m grateful to be given a second chance.”

I have been on cholesterol medication for close to a decade. Although my total cholesterol level seemed within acceptable range most of the time, my HDL is too low. And my BMI score isn’t great either. At 90 kg, I’m close to the borderline between ‘overweight’ and ‘obese.’

Considering my family history, weight, and cholesterol level, I would fall into the ‘high risk’ category for heart disease. Rigorous monitoring and active management would have been necessary. I should have been more diligent in watching my diet and maintaining a healthy weight. Clearly, I have failed at both. And that’s just half the story of my gross negligence in looking after my physical health …

Notes to self

Do not ignore family medical history.

Take early precautions to manage risks factors.

The illusion of ‘fitness’

I haven’t been doing regular health checks, apart from periodic blood tests and doctor consultations for cholesterol management and other non-critical chronic conditions. In February of 2024, as part of a new year resolution to take health more seriously, I underwent a comprehensive health screening that included a treadmill ECG.

The test results showed some abnormality when my heart is under stress. I was supposed to follow up with a cardiologist but procrastinated. I was feeling fine then and did not sense the urgency to act. Moreover, I had been exercising rather regularly – swimming one kilometer almost daily, and even had a quick dip in the ice-cold water in Norway.

“I’m fit as a fiddle,” so I thought. And I was so wrong.

I first noticed the experience of shortness of breath (dyspnea) in June when hiking with my son in Wales. I would slow down and take double the time that he had estimated for completing almost every trail. The ignorant part of me simply attributed that to a lack of fitness. “I really need to exercise more and improve my stamina,” I told myself.

Now, I’m convinced that fitness is not the same as health. There are many cases of marathoners perishing from cardiac arrest during the race. In fact, shortness of breath is a very common tell-tale sign of heart disease, along with chest pain.

As the episodes of dyspnea became more frequent, I suspected something wasn’t right. I began panting heavily after climbing just four flights of stairs. And by the eighth floor, I would need to pause completely to regain my breath. Only then, I began to feel some urgency to seek help.

A long overdue consultation with a cardiologist eventually led to this shocking yet fortunate discovery. Within two weeks from our first meeting, the problem was detected and fixed. I feel so blessed to live in a country with excellent public healthcare.

Early detection is obviously best. But it is still better late than never. In my case, it’s a lifesaver!

Looking back, my potentially fatal assumptions had given me a false sense of comfort. “I am OK,” I thought. But the undeniable truth is that my heart is unwell. With a 100% blockage or chronic total occlusion (CTO) of the right artery, and serious blockages in the left, the likelihood of a heart attack is extremely high. I was a walking timebomb waiting to explode, any time. Thankfully, it’s been defused after two angioplasty procedures and placement of four stents.

Notes to self

Feeling fit doesn’t mean being healthy.

Do not skip annual health screenings.

Early detection can make a big difference.

Consult a specialist promptly, if needed.

With health matters, inaction or procrastination can be fatal.

Accept the present

As expected, my immediate reaction upon learning of the state of my heart was denial. “This can’t possibly be happening. He’s got it wrong,” my inner voice rejected the diagnosis. Then came anger. “Why is this happening to me? This is not fair. I’ve been taking my cholesterol medication daily. Was it for nothing?”

The whole nine yards of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’ five stages of grief kicked in instantly. At that moment, I seemed to have skipped bargaining and depression. Given the urgency to decide on the next course of action, I might have numbed myself momentarily and moved on to the final stage of acceptance rapidly.

“It is what it is. My arteries are clogged, and they need fixing,”I told myself. At least, the cause of my frequent experience of shortness of breath had been identified.

I was reminded of the perennial truth that we can’t change the past, and the future has yet to happen. All that we can really experience is the present. The present is where reality is happening and where life continues unfolding. In the here and now, reality dwells.

But reality isn’t always pleasant or desirable. Who would want a diseased heart? What is, is. What isn’t, isn’t. Resistance or denial would be foolish and futile. The wise thing to do with the present reality is acceptance – complete, unconditional acceptance.

With acceptance comes peace of mind and clarity to make the important decision. I chose to proceed with the complex angioplasty despite the odds. “Will you please notify my wife,” I added, thinking that she should be kept informed of my dire state and the treatment I had chosen. Next, I simply surrendered my fate to the mercy of God and the capable hands of the medical team.

Now that my arteries have been successfully unclogged, I feel incredibly grateful and fortunate. My heart is imperfect and unwell, but it is still beating strongly and keeping me alive to experience abundant beauty, joy, and love. For some, the beating has stopped. I’m glad mine hasn’t.

Examine the past

The chronic total occlusion (CTO) or complete blockage of a coronary artery that I was diagnosed with didn’t happen overnight. It must have taken many years to accumulate that amount of fatty deposit in my arteries.

Many questions had raced through my mind since hearing the diagnosis. How did it get this bad? How have I contributed to my predicament? How could I have missed it? Why haven’t I acted sooner?

But I hadn’t dwelled on them until both angioplasty procedures were completed successfully. I would have been in a different mental and emotional state if a heart bypass was needed. Now that I am in the rest and recovery phase, I have time to reflect more calmly – without anger, self-judgment, self-blame, or regret. I’m grateful to be given a new lease of life and determined to keep my heart healthy.

Spanish philosopher George Santayana once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” I am definitely not keen to repeat the mistakes that got me here. To avoid them, I first need to examine the past with curiosity, and not judgment.

Here’s the list of mistakes I have made.

- Ignoring family medical history and not watching my diet diligently

- Not taking serious actions to reduce weight

- Procrastinating actions to address sleep apnea

- Ignoring early warning signs (i.e. shortness of breath)

- Dismissing health issues as unfitness

- Skipping annual health screening

- Not following up with specialists when risk is identified

It all boils down to poor risk management, particularly those related to heart-health. I have no excuse. It’s not ignorance, but sheer negligence. It’s 100% on me, and there is no one else to be held responsible but me.

Reshape the future

Now that I’ve examined the past and understood how I got my arteries clogged up so badly, what’s next? The wisdom of Danish theologian and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard came to mind: “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forward.”

I take full responsibility for being negligent in taking care of my health in the past. And from here on, I shall take active steps to rechart the course, change the trajectory, and reshape the future in which I continue to live and grow old healthily. I owe that to myself and my loved ones.

Here’s what I have committed …

- Eat a heart-healthy diet. Avoid or consume less saturated fat, salt, sugar, processed food, and alcohol; stop snacking on junk food; limit consumption of red meat; eat more wholesome food, vegetables, legumes, fruits, and white meat.

- Exercise and move regularly. Walk or swim daily; move more throughout the day; engage a personal trainer.

- Improve sleep quality. Use a CPAP machine for sleep apnea and go to bed earlier.

- Enhance mental and emotional well-being. Connect with family and friends more frequently; reinvigorate lost passions; spend more time in nature.

- Manage health risk diligently. Take medications daily; follow up on medical consultations; watch out for early warning signs and act promptly.

Manage risk proactively

Preventive healthcare is all about understanding the risk and taking proactive action to reduce or mitigate them. It’s no surprise that prevention is better than cure, anytime. But we often fail at the former out of ignorance or negligence.

I had been negligent at looking after my heart. The commonly known risk factors contributing to atherosclerosis are as follows.

- Genetics: Family history of heart disease or stroke can increase the risk.

- High Cholesterol Levels: Excess LDL (low-density lipoprotein, or “bad” cholesterol) contributes to plaque formation.

- Obesity: Increases the risk of factors like high blood pressure, diabetes, and abnormal cholesterol levels.

- Sedentary Lifestyle: Lack of physical activity contributes to poor cardiovascular health.

- Poor Diet: Diets high in saturated fats, trans fats, sugar, and sodium contribute to plaque formation.

- High Blood Pressure: Damages the arterial walls, making them more susceptible to plaque buildup.

- Diabetes: High blood sugar levels can damage blood vessels and increase LDL cholesterol.

- Smoking: Promotes inflammation and damages blood vessels.

I rated myself a ‘high’ on the first three factors and either ‘medium’ or ‘low’ on the rest. That put me in the ‘high risk’ category, typically requiring rigorous monitoring and active management.

The good news is that apart from genetics, most if not all other factors are within our control. So far, through a healthier diet, I have shed five kilograms in weight over the last three weeks. It’s an encouraging start, and I have ten more to go.

To share or not to share?

A medical condition is a very private matter, and I’ve deliberated long and hard about sharing it with others. Who should I break the news to? When is the right time? How much detail should I reveal? How should I share it?

Naturally, the first people I notified after my first consultation with the cardiologist are my immediate family members, followed by a few colleagues and friends whom I thought would be most impacted, if something were to go wrong during the angiogram.

After the first angioplasty, I decided to broadcast the news to all my colleagues globally and inform a few clients with whom I was actively engaged. I didn’t want to drop any ball whilst being away on extended medical leave.

Getting work-related concerns out of the way first gave me the mental space to think about the wider circle of family and friends. I started texting a few of them on WhatsApp, and quickly realized that words will spread and soon, and I will be inundated with similar questions and concerns. It would be rude not to reply, but I didn’t want to spend all my rest and recovery time answering text messages. There’s got to be a more efficient way.

So, I decided to share on Facebook – detailing what happened, how I was feeling, what to expect next, and some initial reflections. I hesitated for a few minutes before posting as doubts began to arise. “Why bother sharing this on FB? Do I really want to attract more attention now, when rest is the priority? Would people really want to know about my medical issues? Who would care?”

“Well, at least some people deserve to be informed,” I concluded and hit ‘Post.’ It turned out that the influx of love, encouragement, and support outweighed the risk of overwhelm by intensified attention. It’s comforting to know that family, friends, and colleagues do care, and that my authentic sharing and vulnerability could have a positive impact on some – especially those who have been putting off actions to take care of their health or seek medical attention.

For my own sanity, I’ve set a ‘rule’ to limit my response to each message to simply a Like to indicate that I have read it.Not even a “Thank you” and definitely no back and forth replies like I would normally do. Resisting the temptation to reply to every comment certainly wasn’t easy, but it beats spending the entire day on FB. However, I did reply to private messages on WhatsApp as the volume is more manageable.

Beyond “Get well soon”

From the hundreds of heartwarming responses received over the past few weeks, I have learnt many more ways to show care for someone who is ill besides saying: “Get well soon” or “Wishing you a speedy recovery!”

- Make a phone call

- Send a voice message

- Send a text

- Send a card

- Send gifts – fruit basket, flowers, health products, books, tea.

- Offer to visit – “Let me know when you are ready for visitors.”

- Offer support – “Let me know how I could help. Please reach out if you need anything.”

- Offer to share personal experience

- Check-in intermittently – “How are you feeling now? Hope you are well.”

- Share how the news had impacted you – “I’ve been meaning to schedule an annual health screening but …”

Learning from others’ experience of their major medical issues has been immensely reassuring and uplifting. Many had advised me to stay optimistic and not let the illness stop me from living fully. Their sharing has also inspired me to share my reflections of the entire journey from diagnosis to recovery too.

Epilogue

If I could leave you with one final advice, it would be “mai tu liao” – a Hokkien phrase which means “don’t hesitate; take action immediately” or “don’t delay any further.”

Don’t procrastinate any of these …

- Booking an annual health screening

- Consulting the doctor when you notice something isn’t well

- Starting to eat healthy

- Exercising regularly

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

- Getting sufficient and good quality sleep

- Reaching out to family or friends to express your love and care

Mai tu liao!